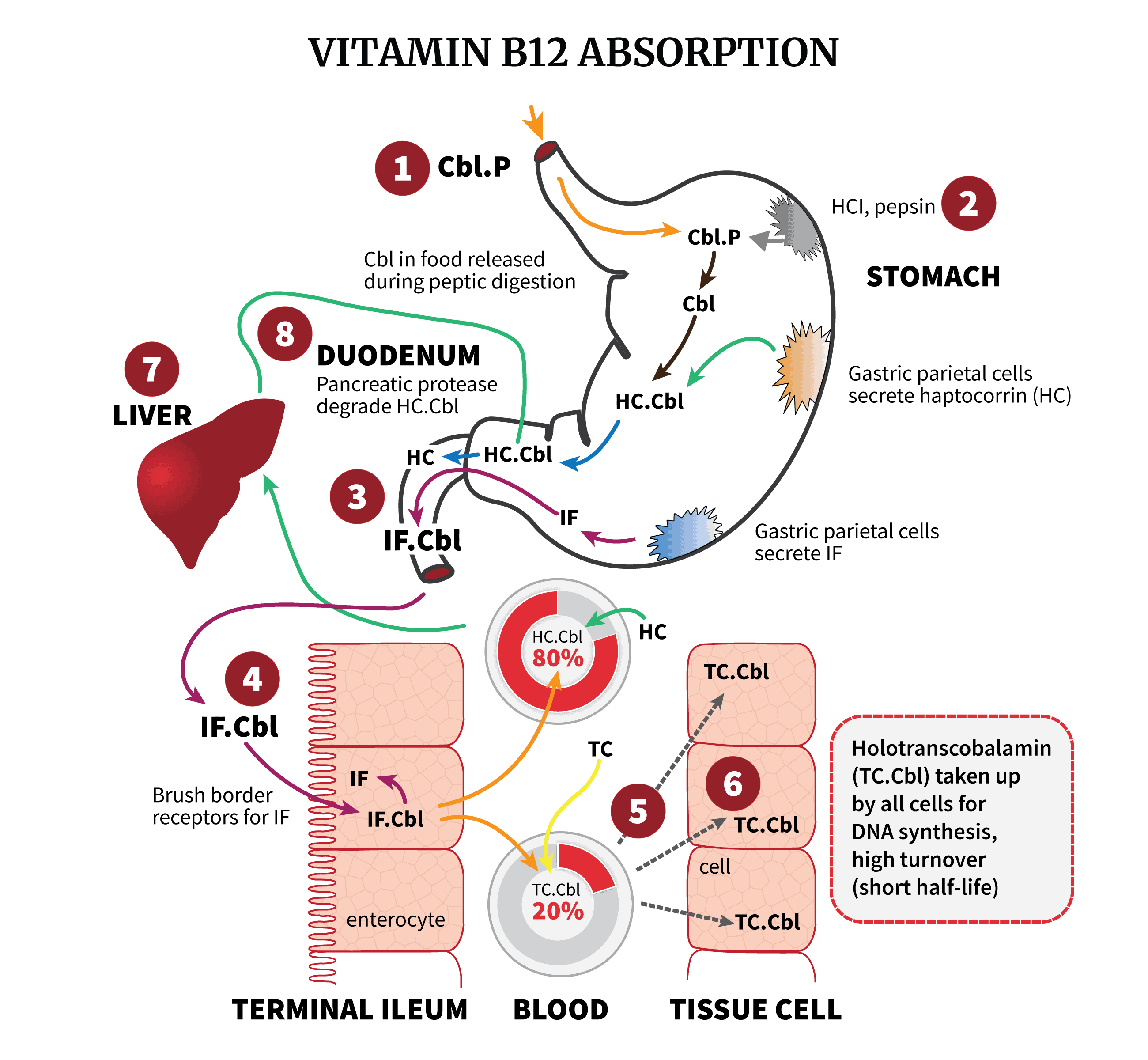

Understanding the pathways through which vitamin B12 is absorbed can help you understand why certain conditions could lead to B12 deficiency. Before we delve into details, let’s start with a nice illustration showing the process, from initial B12 digestion, to the more advanced B12 absorption sites, and finally to cellular delivery:

Vitamin B12 Absorption: Step By Step

So, how is B12 absorbed?

- Food products of animal origin contain vitamin B12. However, the B12 is bound to proteins in these dietary sources. To release the B12 as well as other nutrients, pepsin and acid pH in the stomach will degrade these food proteins.

- Once the B12 is free, it binds to haptocorrin (HC), one of the three B12-binding proteins. HC is produced by the salivary glands and the parietal cells in the stomach. In the duodenum, the pH is now less acidic, which allows pancreatic protease to degrade the HC. Then, B12 (both newly ingested and from the bile duct) is released again, and binds tightly to the intrinsic factor (IF) produced by parietal cells.

- In the mucosal cells of the distal ileum, the B12-IF complex is recognized by special receptors. The B12 passes through, and soon enters the blood, bound to one of two proteins. The majority (70-90%) binds to haptocorrin again, while the rest binds to transcobalamin, forming a complex known as holotranscobalamin (or ‘active B12’). This is the biologically active fraction of vitamin B12 in the blood, as it is in only this form that B12 can be delivered to all the cells of the body.

- Vitamin B12 absorbed in the intestine subsequently gets transported to the liver via the portal system. There is extensive enterohepatic circulation of vitamin B12, and then B12 is transported from the liver, via the bile duct, to the duodenum.

What Could Go Wrong?

Any issue in any step along the way could lead to problems. Obviously, you can see how a diet lacking in sufficient animal products would lead to a higher risk of vitamin B12 deficiency. However, a dietary cause is a relatively uncommon reason. More common is malabsorption due to a number of gastrointestinal risk factors:

- Atrophic gastritis, which increases with age, impairs both the production of the acid and enzymes needed to break down food, and the production of intrinsic factor.

- Pancreatic insufficiency, and of course any surgery which removed any part of the stomach or ileum, could all lead to malabsorption.

- Intestinal diseases such as Crohn’s and celiac disease could cause problems.

- Long-term use of acid suppressants, like proton pump inhibitors and H2 antagonists. These are some of the most widely prescribed drugs among the elderly.

- In true pernicious anemia, where there’s an autoimmune component, there are three different types of antibodies. Those which bind to the B12-IF complex, preventing uptake, those which bind to IF itself, preventing the binding with B12, and those which bind to parietal cells, preventing the production of IF to begin with.

For further information regarding B12 deficiency, see: